Chantel Taylor thinks about the man in his 40s who was supposed to get married the next day, but instead lay hooked up to a ventilator on a COVID-19 unit at the University of Maryland Medical Center in downtown Baltimore.

“In the blink of an eye, he went from about to walk down the aisle to fighting for his life, “ says Taylor, a respiratory therapist who marked four years on the job in the fall of 2020.  She prays that he got to hear the celebration song piped over the intercom for COVID survivors as they left the hospital and the applause of staff lined up to cheer another life saved.

She prays that he got to hear the celebration song piped over the intercom for COVID survivors as they left the hospital and the applause of staff lined up to cheer another life saved.

But she just doesn’t know. That’s part of the sadness the virus leaves in its wake.

The joy of saving a life can never come often enough, especially during a pandemic, and Taylor cherishes every success.

‘To Hear Their Voice’

That is why Taylor and all respiratory therapists are celebrated during Respiratory Care Week. It takes place each October and honors their work and sacrifices, especially in the battle against COVID-19. The annual event recognizes the respiratory care profession and raises awareness for improving lung health around the world.

“The best part is these patients coming off the ventilator … to hear their voice and listen to them thank me that they’re here,” says Taylor.

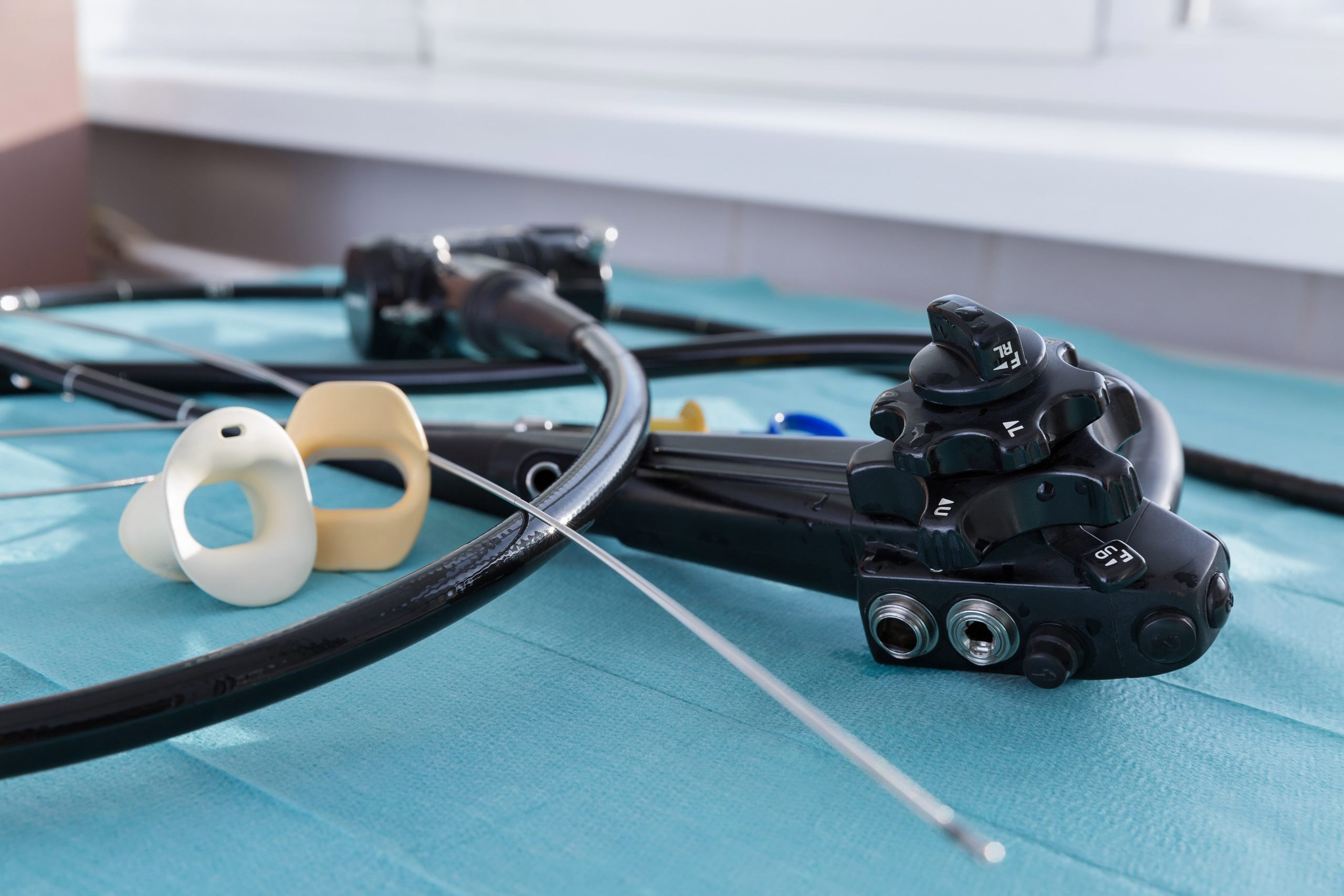

Respiratory therapists work on the front line, right at the edge between life and death. They intubate patients and manage ventilators that whoosh life-saving oxygen into patients’ lungs. Here, too, contaminated droplets from breathing and coughing go airborne and settle on equipment and surfaces, while tiny aerosols float in the air as long as hours.

Danger is all around, especially now.

Instead of simple gowns, they sport N95 masks and powered air purifying respirators, or PAPRs, cumbersome devices that look more like astronaut gear. They also make it hard to hear coworkers and easy to overheat. Back in the spring, RTs were working with half the usual team in the room. Frequently, they were surrounded by strangers from other hospitals there to help.

Taking a Toll

It was a different time on that April day when Taylor, 33, met the critically ill groom. Even less was known about the disease that has claimed more than 2.8 million lives across the globe – more than 553,000 in the U.S. alone.

Taylor, like health professionals worldwide, went to work each day knowing that she would lose patients. At her hospital, there could be 5 to 7 deaths daily on the COVID units, she says.

“Seeing patients die and seeing patients struggle, that took a big toll on a lot of the RTs,” she says.

The hospital’s strict visiting policies – like those around the globe – kept patients isolated, without family or friends. So, she and many other respiratory therapists took on the role of friend on top of their regular job.

“These are patients who are fighting for their lives alone,” she says. “They’re scared. So, you become emotionally attached.”

She and fellow healthcare workers became the lifeline for families, holding iPads and phones so that patients could hear the familiar voices of loved ones who could not visit.

From Healer to Patient

By summer, Taylor, herself, fell victim to the virus – overnight turning from healer to patient. She started feeling sick on July 6th. The next day, she had a fever, body aches and was out of breath.

“I honestly knew I had COVID, but I was in denial, like this can’t be happening to me,” she says.

She took a rapid test at an urgent care center, and it came back positive. She went to the University of Maryland emergency room because her blood pressure had skyrocketed, received a chest X-ray and was sent home.

“The fourth day is when I felt like I wasn’t going to make it through, to the point I called my mom, and I had a conversation with my mom regarding my kids and the life insurance policy, because I was that sick,” she says. “I couldn’t get out of bed. I was that weak. It was horrible.”

She dosed herself with vitamin C, water, orange juice, Gatorade and prayers. Friends left supplies on her doorstep, and she forced herself to get up and walk around.

“I was thinking about work, thinking about my patients and hoping I don’t end up in the ICU,” she says.

About 15 days after she tested positive, her fever broke, and the body aches subsided. She was cleared to return to work about a week later. It was the next month before she regained her sense of taste and smell.

‘Not Going to Lose This Fight’

Taylor was among the lucky ones. At least 21 respiratory therapists have died from the virus in the U.S., according to the American Association for Respiratory Care. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 754 deaths among healthcare workers overall as of mid-October 2020. The real number is likely higher.

Taylor has no idea how she caught the virus. Another RT, who worked on a different unit of the hospital, tested positive at the same time.

There was never a question that Taylor would return to work. She did, however, worry about catching the virus again and taking it home to her 3-year-old son, or her 14-year-old son who suffers from asthma.

“When I took this job, I didn’t think that I would be fighting a pandemic, but I took this job knowing that my role is to take care of patients, to save patients’ lives,” she says. “If I knew coming out of college that I’d be dealing with a situation like this, would I do it again? Yes, I would.”

Today, the Baltimore native wears her fight as a badge of honor – a way to tell patients they can make it.

“You’re not going to lose this fight,’’ she tells them “You’re going to win this battle against this virus. I know exactly how you feel. I know what you’re going through. You’re not alone in this.”’

Inspiring a New Generation

She also uses her experience to inspire second-year respiratory therapy students at Baltimore City Community College about their role in adult critical care.

Some of her students, who range in age from a high schooler to adults in their 50s, are scared. She reminds them about proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and that they can catch the virus anywhere. She warns them not to let fear get in the way of doing their job.

“Don’t be intimidated,” she tells them. “Get in there and learn and help take care of these patients. Get in there and make a difference.”

Taylor is convinced that her experience during the pandemic, both personally and professionally, has made her not just a better respiratory therapist but a better person.

“If I had to take one thing away from this COVID experience, it would be not to take life for granted,” she says. “Enjoy your freedom. Enjoy your family. Love on one another.”